A primer on the FHEW & TFHE schemes

—

This blog post is part of a series about our project on integrity protection for fully homomorphic encryption using zero-knowledge proofs, and was written by Antonio Merino Gallardo as part as a semester project in the PPS Lab.

Next post in this series: Arithmetizing FHE in circom

Fully Homomorphic Encryption: FHEW & TFHE

Fully Homomorphic Encryption (FHE) is a cryptographic primitive that allows one to perform computations on encrypted data. The big efficiency improvements achieved in this primitive in the last few years have fostered the design and development of many privacy-enhancing technologies.

The security of most FHE constructions relies on the introduction of some small random noise into the ciphertexts. While that noise is meant to make it infeasible for attackers to decrypt without knowing the key, it also raises some issues. The noise increases when performing computations and ciphertexts can only withstand a certain amount of noise before they become useless. In 2009, Gentry solved this problem by introducing the so-called bootstrapping procedure that lowers the noise of a ciphertext without having access to the decryption key, hence constructing the first fully homomorphic encryption scheme [Gen09].

Since Gentry's work, a variety of FHE schemes have been proposed with important efficiency improvements . As bootstrapping is one of the main bottlenecks, different approaches have been presented to deal with this costly operation, such as simultaneously refreshing the noise of many ciphertexts in the same bootstrapping or performing as many operations as possible before bootstrapping. The FHEW scheme [DM15] focuses instead on simplifying the setting and supports a fast bootstrapping procedure tailored for ciphertexts encrypting a single bit. The TFHE scheme [CGGI16], [CGGI20] subsequently improved on it and is part of the state of the art in terms of FHE schemes for boolean and short integer operations (up to 8 bits). More recently, two new variants have been proposed in [LMK+23] and [XZD+23].

There are several explanations of the fundamentals of FHEW and/or TFHE schemes ([DM15], [CGGI20], [MP21], [J22], [Chi22]). Implementation-wise the main references are OpenFHE's implementation of FHEW and TFHE [OpenFHE], and ZAMA's implementation of TFHE [TFHE-rs]. Despite the variety of resources, the use of different notations and levels of abstraction in the explanations and the highly optimized code of the implementations make it hard to relate them to each other. The aim of this blog post is thus to bridge the gap between theory and practice by providing a thorough yet simple description of all the operations that these schemes involve. With that in mind, our focus will not be that much on why they work but rather on how they work with descriptions close to the implementation level.

Particularly useful was the work by Daniele Micciancio and Yuri Polyakov [MP21] describing the differences between FHEW and TFHE in a unified framework. That is the framework that this post will follow. In particular, we will consider both schemes in the integer setting (instead of describing TFHE in the Torus setting), we will consider ternary secret keys for both schemes (instead of the binary keys that TFHE originally proposed but for which there is less assurance about their security) and we will describe FHEW with certain optimizations of TFHE that can be applied to both schemes.

Functional Boostrapping - Overview

The FHEW and TFHE schemes focus on boolean and short integer computations and stand out for their fast bootstrapping procedure. Interestingly, their bootstrapping operation not only refreshes the noise of the ciphertext but it can also be configured to compute a function at the same time. That is the reason why it is also referred to as functional bootstrapping or programmable bootstrapping.

Circuits can be generally obtained by the application of several functional bootstrapping operations. For instance, any boolean circuit can be expressed in terms of NAND gates, and a bootstrapped NAND gate can be constructed by applying a functional bootstrapping to the sum of two encrypted bits - we will see how at the end of the post. This use of the bootstrapping operation is called gate bootstrapping.

In essence, the description of the FHEW and TFHE schemes comes down to the description of their functional bootstrapping procedures. Their structure is as follows:

We can distinguish two major phases in functional bootstrapping: the accumulator phase, which deals with the more complex RLWE and RGSW ciphertexts, and the LWE phase, which deals with the simpler LWE ciphertexts.

It is also important to note that the only algorithmic difference between FHEW and TFHE is the accumulator update, also known as the blind rotation procedure. The rest of the operations are the same for both schemes.

For expository purposes, we will start by describing the simpler LWE phase before delving into the accumulator.

LWE phase

An important part of the functional bootstrapping only deals with LWE ciphertexts. Let's see what these ciphertexts look like and what operations are performed with them.

LWE ciphertexts

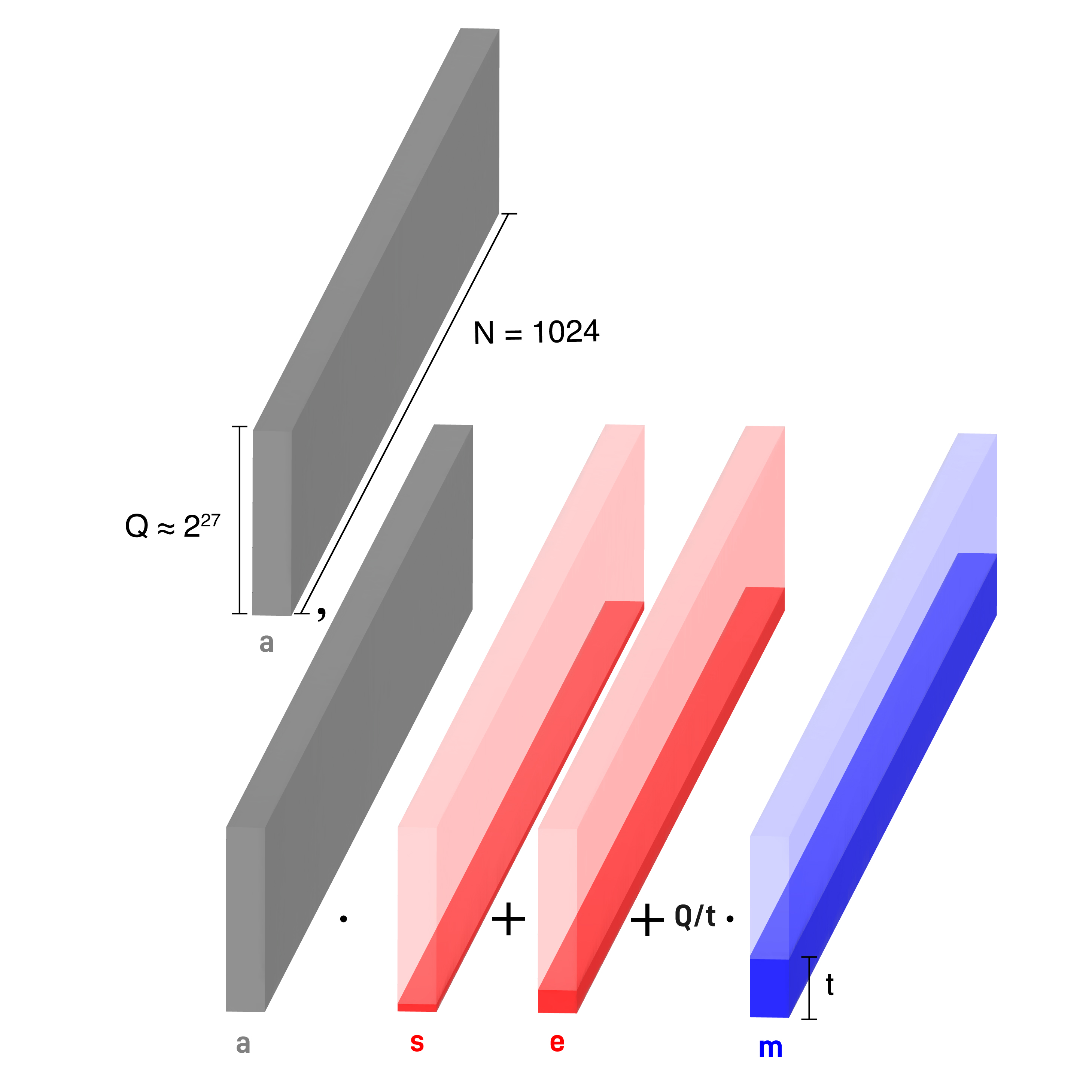

Given a message $m \in \mathbb{Z}_t$, an LWE encryption of $m$ under a key $s \in \mathbb{Z}_q^n$ is an LWE ciphertext of the form:

$$ (a, b) = \left(a, (a \cdot s + \tilde{m} + e)\mod q \right) \in \mathbb{Z}_q^{n} \times \mathbb{Z}_q $$

where

- $\tilde{m} = (q/t)m \in \mathbb{Z}_q$ is the encoding of m

- $n$ is the dimension (in practice $n \approx 512$)

- $t$ is the message modulus ($t = 2$ for binary messages)

- $\mathbb{Z}_t$ is the message space

- $q$ is the ciphertext modulus (in practice $q = 1024$)

- $s \in \mathbb{Z}_q^n$ is the key (in practice we will work with keys in the subset $\mathbb{Z}_3 ^n \cong \{-1,0,1\}^n$)

- $a \leftarrow \mathbb{Z}_q^n$ is a uniformly at random sampled mask

- $e \in \mathbb{Z}_q$ is a small noise or error sampled at random

We define the error of a ciphertext to be $\mathrm{err}(a, b)=(b-a \cdot s-\tilde{m}) \mod q$ and will consider it to be in the centered interval $[-q/2, q/2)$. Note that for a fresh encryption we have $\mathrm{err}(a, b)=e$. We will say that $(a,b)$ is an LWE encryption of $\tilde{m}$ or $(a, b) \in \mathrm{LWE}_s^q(\tilde{m})$ as long as $|\mathrm{err}(a, b)| < q/(2t)$.

Given a ciphertext $(a', b') \in \mathbb{Z}_q^{n+1}$, it is decrypted by computing:

$$ \tilde{m}' = b-a \cdot s $$

and then performing a decoding operation that corrects the error and recovers the encoded message. In this case, we would recover the message as

$$m' = \lfloor (t/q)\tilde{m} \rceil \mod t.$$

The rounding operation takes care of the small added noise. However, to correctly recover the message the noise needs to be $|\mathrm{err}(a',b')| < q/(2t)$. The noise growth that occurs when performing computations with ciphertexts justifies the need for refreshing their noise with a bootstrapping procedure.

The security of this encryption scheme relies on the hardness assumption of the Learning With Errors (LWE) problem. The idea is that the value $a \cdot s + e$ acts as a one-time pad to hide the encoded message $\tilde{m}$.

Addition & Subtraction

The LWE encryption scheme is additively homomorphic. Given two LWE ciphertexts $(a, b) \in \mathrm{LWE}_s^q(\tilde{m}), (a', b') \in \mathrm{LWE}_s^q(\tilde{m}')$ then

$$ (a'{}', b'{}') = (a, b) + (a', b') = (a + a', b + b') \in \mathbb{Z}_q^{n+1}, $$

where the sum of the masks $a + a'$ is performed component-wise, and all the sums are performed modulo $q$. We have that $\mathrm{err}(a'{}',b'{}')=\mathrm{err}(a,b)+\mathrm{err}(a',b')$, and so we will have $(a'{}', b'{}') \in \mathrm{LWE}_s^q(\tilde{m}+\tilde{m}')$ as long as $|\mathrm{err}(a,b)+\mathrm{err}(a',b')| < q/(2t).$

Similarly, LWE ciphertexts can be subtracted by considering the subtraction modulo $q$.

Modulus Switching

The modulus switching procedure allows to change the modulus of an LWE ciphertext.

Given $(a,b) \in \mathrm{LWE}^Q_s(\tilde{m})$ encrypted with modulus $Q$ and a target modulus $q$, the following operation will be performed to all the components of the ciphertext:

$$ [x]_{Q:q} = \lfloor qx/Q \rceil $$

Overall,

$$ \mathrm{ModSwitch}(a, b) = (([a_1]_{Q:q}, \dots, [a_n]_{Q:q}), [b]_{Q:q}) \in \mathrm{LWE}^q_s(\tilde{m}). $$

Key Switching

The key-switching procedure allows one to change the key under which an LWE ciphertext is encrypted. This method is parametrized by a key switching modulus $Q_{ks}$ (in practice $Q_{ks} \approx 2^{14}$) and a key switching base $B_{ks}$ (in practice $B_{ks} \approx 128$). We can denote the number of digits of $Q_{ks}$ under base $B_{ks}$ as $dks = \lceil \log_{B_{ks}}Q_{ks} \rceil$.

Given an LWE ciphertext $(a,b) \in \mathrm{LWE}^{Q_{ks}}_z(\tilde{m})$ under secret key $z \in \mathbb{Z}_{Q_{ks}}^N$ and a key switching key $\mathrm{KSK}$, this operation returns an LWE ciphertext in $\mathrm{LWE}^{Q_{ks}}_s(\tilde{m})$ under secret key $s \in \mathbb{Z}_{Q_{ks}}^n$.

The key switching key is of the form $\mathrm{KSK}={\mathrm{ksk}_{i,j,v}}$ where:

$$ k_{i,j,v} \in \mathrm{LWE}^{Q_{ks}}_s(vz_iB^j_ {ks}), $$

$$ i \in \{0,\dots,N-1\}, ~ j \in \{0,\dots, dks-1 \}, ~ v \in \{0,\dots,B_{ks}-1\}. $$

Note that this method not only changes the encryption key but also the dimension of the LWE ciphertext from a dimension $N$ (in practice $N = 1024$) to a dimension $n$ (in practice $n \approx 512$).

The key switching works by decomposing under the base $B_{ks}$ each component of the mask $a$ of the input LWE ciphertext:

$$ a_i = \sum_{j=0}^{dks-1} a_{i,j}B^j_ {ks}, i \in \{0,\dots, N-1\}, a_{i,j} \in \{0,\dots,B_{ks}-1\}. $$

By obtaining the decomposition, the output of the method is:

$$ \mathrm{KeySwitch}((a,b), \mathrm{KSK}) = (\textbf{0},b) - \sum_{i,j}k_{i,j, a_{i,j}} $$

We can consider the LWE ciphertexts to be pairs of the form (a[n], b) and the key switching key to be a 3D array of size $N \times dks \times B_{ks}$ whose components are LWE ciphertexts.

// Key Switching

input: (a[N], b), KSK[N][dks][Bks] of (x[n], y)

output: (a'[n], b')

(a', b') := ([0,..,0], b)

for i := 0 to N-1

c := a[i]

for j := 0 to dks-1

digit := c % Bks

key := KSK[i][j][digit]

(a', b') := (a', b') - key

c := c / Bks

return (a', b') Accumulator Phase

The accumulator allows one to perform the core operation of the functional bootstrapping, i.e., given a function $\mathrm{f}$ and an LWE ciphertext encrypting some encoded message $\tilde{m}$, it will return an LWE ciphertext with less noise encrypting $\mathrm{f}(\tilde{m})$. That LWE ciphertext that will be extracted from the accumulator will have a different dimension, modulus, and encryption key from the input ciphertext. That is the reason why a later phase of modulus and key switching is needed. Note that the function $\mathrm{f}$ can be set to be the identity function if we just want to refresh the noise of the ciphertext.

The rough idea of the accumulator is to initialize a polynomial that stores the images of the function $\mathrm{f}$ in its coefficients. The update or blind rotation step will rotate the coefficients of the polynomial according to the given LWE ciphertext. Finally, the constant term of the polynomial will be extracted to construct the output LWE ciphertext. The part where FHEW and TFHE differ is in how they perform the update step.

In this phase, we will work with more complex ciphertexts that deal with polynomials, and that will allow us to multiply ciphertexts: Ring-LWE (RLWE) and Ring-GSW (RGSW) ciphertexts.

RLWE ciphertexts

The Ring-LWE (RLWE) scheme is analogous to the LWE scheme but uses polynomials instead of elements in $\mathbb{Z}_q$. We will only consider RLWE ciphertexts with one polynomial in the mask (instead of $n$ components as we did for LWE). Additionally, we will assume that messages are already encoded to the proper space.

The polynomials we will work with are elements of the cyclotomic ring $\mathcal{R} = \mathbb{Z}[X]/(X^N+1)$. As such, they can be expressed as polynomials of degree strictly less than N. Instead of working with coefficients in $\mathbb{Z}$, we will usually restrict them to $\mathbb{Z}_Q$ for some modulus $Q \in \mathbb{N}$. Hence, we will consider $\mathcal{R}_Q = \mathbb{Z}_Q[X]/(X^N+1)$. Note that we can identify $\mathcal{R}_Q$ with $\mathbb{Z}_Q^N$ and so implementation-wise we can see an element of $\mathcal{R}_Q$ as an array of $N$ components each of them storing one coefficient of the polynomial as an integer in ${0,.., Q-1}$.

Given a message $m \in \mathcal{R}_Q$, an RLWE ciphertext encrypting $m$ can be computed as:

$$ (A, B) = (A, A \cdot z + m + e) \in \mathcal{R}_Q \times \mathcal{R}_Q, $$

where

- $N$ is the dimension of the cyclotomic ring (in practice $N = 1024$)

- $Q$ is the prime ciphertext modulus (in practice $Q \approx 2^{27}$)

- $z \in \mathcal{R}_Q$ is the key (in practice we will work with keys in the "subset" $\{-1,0,1\}^N$)

- $a \leftarrow \mathcal{R}_Q$ is a uniformly at random sampled mask (by sampling each of the N coefficients of the polynomial)

- $e \in \mathcal{R}_Q$ is a small noise sampled at random

We will say that $(A, B)$ is an RLWE encryption of $m$ or that $(A, B) \in \mathrm{RLWE}_z^Q(m)$ as long as the noise is within boundaries.

The decryption procedure is analogous to that of LWE and the security of the scheme is based on the Ring-Learning With Errors (RLWE) hardness assumption which is analogous to the LWE one.

RGSW ciphertexts

Ring-GSW (RGSW) ciphertexts are based on the work from [GSW13] and can be seen as a collection of RLWE ciphertexts. They are parametrized by a gadget base $B_G$ (in practice $B_G \approx 128$) and we can denote the number of digits of $Q$ under base $B_G$ as $dg = \lceil \log_{B_G}(Q)\rceil$.

The RLWE encryption scheme

$$\mathrm{RLWE}_z^Q(m) \subseteq \mathcal{R}_Q \times \mathcal{R}_Q,$$

can be extended to the following RLWE' scheme

$$\mathrm{RLWE}_z^{'Q}(m) = (\mathrm{RLWE}_z^Q(m), \mathrm{RLWE}_z^Q(B_Gm), \dots, \mathrm{RLWE}_z^Q(B_G^{dg-1}m)) \subseteq (\mathcal{R}_Q^2)^{dg}$$

and finally, we can obtain the RGSW ciphertexts as

$$\mathrm{RGSW}_z^Q(m)=(\mathrm{RLWE}_z^{'Q}(-s \cdot m), \mathrm{RLWE}_z^{'Q}(m)) \subseteq ((\mathcal{R}_Q^2)^{dg})^2$$

Initialization

Given the second component $b \in \mathbb{Z}_q$ of an LWE ciphertext and a function $\mathrm{f}: \mathbb{Z}_q \to \mathbb{Z}_Q$, the accumulator is initialized to a noiseless encryption $(0,p) \in \mathrm{RLWE}(p)$ of the polynomial

$$ p(X) = \sum_{i=0}^{q/2} f(b-i) \cdot X^{i \cdot (2N/q)} $$

Note that the range of the input function $\mathrm{f}$ is $\mathbb{Z}_Q$, so in general we will need to rescale the values of the images when working with a function mapping $\mathbb{Z}_q \to \mathbb{Z}_q$. We will see an example of this when going over the bootstrapped NAND gate.

Regarding the factor $2N/q$ in the exponent, it comes from the fact that we are dealing with a sparse embedding of $\mathbb{Z}_Q/(X^{q/2} + 1)$ to $\mathbb{Z}_Q/(X^{N} + 1)$. For this, we need to impose that $q$ divides $2N$.

A pseudocode description of the method follows:

// Accumulator Initialization

input: b, f[q]

output: (A[N], B[N])

(A, B) := ([0,..,0], [0,..,0])

for i := 0 to q/2-1

B[i * (2*N/q)] := f[(b-i) % q]

return (A, B) Looking closely at the method, only half of the values of $\mathrm{f}$ are used when initializing the accumulator. This points to one important requirement of the accumulator regarding the properties of $\mathrm{f}$. In reality, we cannot use any function $\mathrm{f}: \mathbb{Z}_q \to \mathbb{Z}_Q$, but rather, one that is negacyclic, i.e., one that satisfies

$$\mathrm{f}(v + q/2) = -f(v)$$

for all $v \in \mathbb{Z}_q$. Despite this restriction, we will be able generally to adapt an arbitrary function to one that is negacyclic.

Update

The accumulator update or blind rotation is the core operation of the bootstrapping as well as its main bottleneck. It is a procedure that FHEW and TFHE perform differently: FHEW follows the approach from Alpein-Sherif-Peikert [AP14] and TFHE the one from Gama-Izabachene-Nguyen-Xie [GINX16].

Given as inputs:

- the mask $a \in \mathbb{Z}_q^n$ of an LWE ciphertext $(a, b) \in \mathrm{LWE}_s^q(m)$,

- the initialized accumulator $(A, B) \in \mathrm{RLWE}_z^Q(\sum_{I=0}^{q/2} f(b-i) \cdot X^{i \cdot (2N/q)})$ and

- the bootstrapping key $\mathrm{BSK}$ consisting of a collection of RGSW ciphertexts encrypting the components of the key $s \in \mathbb{Z}_q^n$ under key $z \in \mathcal{R}_Q$,

the blind rotation procedure returns an updated accumulator:

$$(A', B') \in \mathrm{RLWE}_z^Q\left(\sum_{i=0}^{q/2} f(b-i) \cdot X^{(i-\textbf{a} \cdot \textbf{s}) \cdot (2N/q)}\right).$$

The difference in content between the input and output ciphertexts is that the latter is multiplied by the monomial $X^{(-a \cdot s) \cdot (2N/q)}$. That factor essentially performs a rotation of the coefficients of the polynomial, taking into account that operations are computed modulo $X^N+1$ (so $X^N \equiv -1$ and $X^{2N} \equiv 1$).

Fundamentally, FHEW and TFHE differ in how they multiply the content of the accumulator by $X^{(-a_j \cdot s_j) \cdot (2N/q)}$ for each step $j \in {0,\dots,n-1}$.

In both cases, the schemes rely on a multiplication operation between RLWE and RGSW ciphertexts. Let's assume for now that we know how to multiply them and let

$$\odot : \mathrm{RLWE} \times \mathrm{RGSW} \to \mathrm{RLWE}$$

denote that operation.

FHEW's Accumulator Update

The accumulator update of FHEW is parametrized by a refreshing base $B_r$ (in practice $B_r \approx 32$). We can denote the number of digits of $q$ in the base $B_r$ as $dr = \lceil \log_{B_r}q \rceil$.

Given as inputs:

- the mask $a \in \mathbb{Z}_q^n$ of an LWE ciphertext $(a, b) \in \mathrm{LWE}_s^q(m)$,

- the initialized accumulator $(A, B) \in \mathrm{RLWE}_z^Q(\sum_{I=0}^{q/2} f(b-i) \cdot X^{i \cdot (2N/q)})$ and

- the bootstrapping key $\mathrm{BSK}={\mathrm{bsk}_{i,j,v}}$ where

$$ \mathrm{bsk}_{i,j,v} \in \mathrm{RGSW}_z^Q(X^{vB_r^js_i \cdot (2N/q)}),$$

$$i \in \{0,\dots,n-1\}, j \in \{0,\dots,dr-1\}, v \in \{0,\dots,B_r-1\}$$

the blind rotation procedure returns an updated accumulator:

$$(A', B') \in \mathrm{RLWE}_z^Q\left(\sum_{i=0}^{q/2} f(b-i) \cdot X^{(i-\textbf{a} \cdot \textbf{s}) \cdot (2N/q)}\right).$$

This procedure has a similar idea to the key switching previously explained. For each $i \in {0,\dots,n-1}$ we will decompose $-a_i \mathrm{mod} q$ under the base $B_r$, i.e.,

$$-a_i \equiv \sum_{j=0}^{dr-1}a_{i,j}B_r^j \mod q.$$

Then at each step $(i,j) \in {0,\dots,n} \times {0,\dots,dr-1}$ we will update the current value $\mathrm{ACC}$ of the accumulator as $\mathrm{ACC} := \mathrm{ACC} \odot \mathrm{bsk}_{i,j,a_{i,j}}$.

As for the pseudocode version:

// Accumulator Update - FHEW

input: a[n], (A[N], B[N]) in RLWE, BSK[n][dr][Br] of RGSW ciphertexts

output: (A'[N], B'[N]) in RLWE

(A', B') := (A, B)

for i := 0 to n-1

c := (-a[i] % q)

for j := 0 to dr-1

digit := c % Br

key := BSK[i][j][digit]

(A', B') := (A', B') ⊙ key

c := c/Br

return (A', B')Note that whenever $a_{i,j}=0$ for some $i \in {0,\dots,n-1},j \in {0,\dots dr-1}$, the respective $\mathrm{bsk}_{i,j,a_{i,j}}$ will just be an encryption of $1$. In that case, the multiplication $(A',B') \odot \mathrm{bsk}_{i,j,a_{i,j}}$ is redundant. Therefore, we can omit from $\mathrm{BSK}$ all the ciphertexts of the form $\mathrm{bsk}_{i,j,0}$ and only update the accumulator for those $(i,j)$ for which $a_{i,j} \neq 0$.

TFHE's Accumulator Update

The accumulator update procedure that we are going to describe is slightly different from TFHE's original version. The original construction strongly relies on the use of binary secret keys, but their security is currently not well understood. While the construction can be adapted to keys with larger components, the performance decays as the size increases. In such situations, the Homomorphic Encryption Standard [ACC+18] mentions the option of using ternary secret keys, i.e., with components uniformly distributed in ${-1, 0, 1}$. Fortunately, the performance of TFHE with ternary keys is close to the binary case by following the approach introduced in [JP22]. That is the version that OpenFHE implements and the one that we are going to cover.

Given as inputs:

- the mask $a \in \mathbb{Z}_q^n$ of an LWE ciphertext $(a, b) \in \mathrm{LWE}_s^q(m)$,

- the initialized accumulator $(A, B) \in \mathrm{RLWE}_z^Q(\sum_{I=0}^{q/2} f(b-i) \cdot X^{i \cdot (2N/q)})$ and

- the bootstrapping key $\mathrm{BSK}'={\mathrm{bsk}'_{i,j}}$ where

$$ \mathrm{bsk}'_{i,j} \in \mathrm{RGSW}_z^Q(x_{i,j}),$$

$$s_i=x_{i,1} - x_{i,-1}, x_{i,j} \in \{0,1\}, x_{i,-1} \cdot x_{i,1} = 0,$$

$$i \in \{0,\dots,n-1\}, j \in \{-1, 1\}$$

the blind rotation procedure returns an updated accumulator:

$$(A', B') \in \mathrm{RLWE}_z^Q\left(\sum_{i=0}^{q/2} f(b-i) \cdot X^{(i-\textbf{a} \cdot \textbf{s}) \cdot (2N/q)}\right).$$

The bootstrapping key $\mathrm{BSK}'$ is quite different from the bootstrapping key $\mathrm{BSK}$ from FHEW. In this case, we are leveraging the fact that $s \in {-1,0,1}^n$ to decompose each of its components as $s_i = x_{i,1} - x_{i,-1}$ where:

- If $s_i = -1$, then $x_{i,-1} = 1$ and $x_{i,1}=0$.

- If $s_i = 0$, then $x_{i,-1} = 0$ and $x_{i,1}=0$.

- If $s_i = 1$, then $x_{i,-1} = 0$ and $x_{i,1}=1$.

We will update the accumulator sequentially for each component $s_i$ of the mask. In each step $i \in {0,\dots,n-1}$, the value $\mathrm{ACC}$ of the accumulator will be updated as:

$$\mathrm{ACC} := \mathrm{ACC} + (X^{-a_i \cdot (2N/q)}-1) \cdot (\mathrm{ACC} \odot \mathrm{bsk}'_{i,1}) + (X^{a_i \cdot (2N/q)}-1) \cdot (\mathrm{ACC} \odot \mathrm{bsk}'_{i,-1}).$$

To see this in the pseudocode version:

// Accumulator Update - TFHE

input: a[n], (A[N], B[N]) in RLWE, BSK'[n][2] of RGSW ciphertexts

output: (A'[N], B'[N]) in RLWE

(A', B') := (A, B)

for i := 0 to n-1

exp1 := (-a[i] % q) * (2*N/q)

exp2 := (-exp) % 2*N

prod1 := (A', B') ⊙ BSK'[i][0]

prod2 := (A', B') ⊙ BSK'[i][1]

(A', B') := (A', B') + (X^exp1 - 1)*prod1 + (X^exp2 - 1)*prod2

ENDFOR

RETURN (A', B')RLWE-RGSW multiplication

As we can see from both versions of the blind rotation procedure, they strongly rely on a multiplication operation

$$\odot : \mathrm{RLWE} \times \mathrm{RGSW} \to \mathrm{RLWE}$$

between ciphertexts. We will now see what this operation looks like in detail.

Recall that

$$\mathrm{RLWE}_z^Q(m) \subseteq \mathcal{R}_Q^2,$$

and from them, we can construct

$$\mathrm{RLWE}_z^{'Q}(m) = (\mathrm{RLWE}_z^Q(m), \mathrm{RLWE}_z^Q(B_Gm), \dots, \mathrm{RLWE}_z^Q(B_G^{dg-1}m)) \subseteq (\mathcal{R}_Q^2)^{dg}$$

and

$$\mathrm{RGSW}_z^Q(m)=(\mathrm{RLWE}_z^{'Q}(-s \cdot m), \mathrm{RLWE}_z^{'Q}(m)) \subseteq ((\mathcal{R}_Q^2)^{dg})^2$$

where $B_G$ is the gadget base and $dg = \lceil \log_{B_G}(Q)\rceil$.

The first step of the multiplication is to perform a signed decomposition of all the coefficients of the two polynomials of the $\mathrm{RLWE}$ ciphertext.

For an integer $x \in \mathbb{Z}_Q$, its signed decomposition is of the form $(x_0,\dots,x_{dg-1})$, where

$$x = \sum_{i=0}^{dg-1} x_iB_G^i(\mathrm{mod} Q), x_i \in [0,B_G/2) \cup [Q-B_G/2, Q).$$

As a reference, in a standard digit decomposition, we would have $x_i \in [0, B_G].$

When applying a signed decomposition to a ciphertext $(A, B) \in \mathcal{R}_Q^2$, we obtain $2d_g$ polynomials $(A_0, B_0, \dots, A_{dg-1}, B_{dg-1}) \in \mathcal{R}_Q^{2dg}$ such that

$$A = \sum_{i=0}^{dg-1} A_iB_G^i(\mathrm{mod}Q),B = \sum_{i=0}^{dg-1} B_iB_G^i(\mathrm{mod}Q),$$

and all the coefficients of $A_i$ and $B_i$ are in $[0,B_G/2) \cup [Q-B_G/2, Q)$ for all $i \in {0,\dots,dg-1}$.

Parallelly, given an RGSW ciphertext

$$(c, c') \in \mathrm{RLWE}_z^{'Q}(-s\cdot m) \times \mathrm{RLWE}_z^{'Q}(m) \subseteq \mathrm{RGSW}_z^Q(m) \subseteq ((\mathcal{R}_Q^2)^{dg})^2,$$

we can express it as

$$(c_0, c'_0, \dots, c_{dg-1}, c'_{dg-1}) \in (\mathcal{R}_Q^2)^{2dg},$$

where each $c_i$ and $c_i'$ is an RLWE ciphertext containg two polynomials for $i \in {0,\dots,dg-1}$.

Finally, building upon the multiplication between a polynomial and an RLWE ciphertext,

$$(\cdot): \mathcal{R}_Q \times \mathrm{RLWE} \to \mathrm{RLWE}$$

$$p \cdot (A, B) := (p \cdot A, p \cdot B),$$

we can construct the multiplication between RLWE and RGSW ciphertexts as

$$(\odot) : \mathrm{RLWE} \times \mathrm{RGSW} \to \mathrm{RLWE}$$

$$(A, B) \odot (c, c'):= A_0 \cdot c_0+B_0 \cdot c'_0 + \cdots + A_{dg-1} \cdot c_{dg-1} + B_{dg-1} \cdot c'_{dg-1}$$

where $(A_0, B_0, \dots, A_{dg-1}, B_{dg-1}) \in \mathcal{R}_Q^{2dg}$ is the signed decomposition of $(A, B)$ and $(c_0, c'_0, \dots, c_{dg-1}, c'_{dg-1}) \in (\mathcal{R}_Q^2)^{2dg}$ is the expanded expression of $(c, c')$. Note that we are essentially performing a dot product between those two vectors.

Overall, we now know how to reduce that essential multiplication of ciphertexts to multiplications of polynomials in $\mathcal{R}_Q = \mathbb{Z}_Q[X]/(X^N+1)$. While we could just multiply polynomials via the schoolbook method and then reduce modulo $(X^N+1)$, the problem of multiplying polynomials in a ring has been deeply studied and there are far more efficient ways to do so. In particular, one can resort to the Number Theoretic Transform (NTT).

The NTT is a linear transformation that takes a polynomial in coefficient form and converts it to evaluation form. In particular, given a polynomial in $\mathcal{R}_Q$, which has N coefficients, the NTT converts it to an array of $N$ evaluation points in $\mathbb{Z}_Q$. The advantage of such transformation is that polynomials in evaluation form can be multiplied component-wise, requiring a total of $N$ multiplications in $\mathbb{Z}_Q$.

The inverse of the NTT is another linear transformation that we will denote by INTT and which is really close algorithmically to the NTT. By combining both transformations and the component-wise product ($\circ$), we can efficiently obtain the product of two polynomials $p_1, p_2 \in \mathcal{R}_Q$ as

$$p_1 \cdot p_2 = \mathrm{INTT}(\mathrm{NTT}(p_1) \circ \mathrm{NTT}(p_2)).$$

This is the method that we will apply to multiply polynomials in the context of the RLWE-RGSW multiplication.

We have to note that the special form of the ring that we are working with, i.e., $\mathbb{Z}_Q[X]/(X^N+1)$ where $N$ is a power of 2 and $Q \equiv 1(\mathrm{mod}~ 2N)$, requires a special type of NTT. We refer the interested reader to [LZ22].

Integrating the NTT in the accumulator update

We now describe the complete versions of the accumulator update integrating the NTT in the algorithms.

Since we want to multiply polynomials in evaluation form, we need to apply the NTT to the $2dg$ polynomials that come out of the signed decomposition, and we assume that the RGSW ciphertexts are directly provided with all its polynomials in evaluation form.

For the following iteration we need the polynomials to be again in coefficient form, so we will have to apply the INTT to the two polynomials of the accumulator right after the multiplication.

With that in mind, the final versions of the accumulator update can be described as follows:

// Accumulator Update - FHEW

input: a[n], (A[N], B[N]) in RLWE, BSK[n][dr][Br] of RGSW ciphertexts ([2*dg][2][N])

output: (A'[N], B'[N]) in RLWE

(A', B') := (A, B)

for i := 0 to n-1

c := (-a[i] % q)

for j := 0 to dr-1

digit := c % Br

key := BSK[i][j][digit]

dec := SignedDecompose(A', B') // dec[2*dg][N]

dec := [NTT(x) for x in dec]

A' := sum(dec[i] ⚬ key[i][0] for i in [0, 2*dg-1])

B' := sum(dec[i] ⚬ key[i][1] for i in [0, 2*dg-1])

(A', B') := (INTT(A'), INTT(B'))

c := c/Br

return (A', B')// Accumulator Update - TFHE

input: a[n], (A[N], B[N]) in RLWE, BSK'[n][2] of RGSW ciphertexts ([2*dg][2][N])

output: (A'[N], B'[N]) in RLWE

(A', B') := (A, B)

for i := 0 to n-1

exp1 := (-a[i] % q) * (2*N/q)

exp2 := (-exp) % 2*N

binom1 := NTT(X^exp1 - 1)

binom2 := NTT(X^exp2 - 1)

key1 := BSK'[i][0]

key2 := BSK'[i][1]

dec := SignedDecompose(A', B') // dec[2*dg][N]

dec := [NTT(x) for x in dec]

prod1[0] := sum(dec[i] ⚬ key1[i][0] for i in [0, 2*dg-1])

prod1[1] := sum(dec[i] ⚬ key1[i][1] for i in [0, 2*dg-1])

prod2[0] := sum(dec[i] ⚬ key2[i][0] for i in [0, 2*dg-1])

prod2[1] := sum(dec[i] ⚬ key2[i][1] for i in [0, 2*dg-1])

(A'{}', B'{}') := (binom1 ⚬ prod1[0], binom1 ⚬ prod1[1])

(A'{}', B'{}') := (A'{}', B'{}') + (binom2 ⚬ prod2[0], binom2 ⚬ prod2[1])

(A'{}', B'{}') := (INTT(A'{}'), INTT(B'{}'))

(A', B') := (A', B') + (A'{}', B'{}')

return (A', B')Note that in TFHE only a signed decomposition and a subsequent NTT to the array are needed for the two RLWE-RGSW multiplications that take place.

Another interesting remark is that in practice, instead of a signed decomposition, an approximate signed decomposition that ignores the first digit of the decomposition is performed. This approximate version allows one to save 2 NTTs per iteration (one per polynomial that is decomposed) at the cost of some tolerable additional error.

Extraction

Given the accumulator

$$(A, B) \in \mathrm{RLWE}_z^Q\left(\sum_{i=0}^{q/2} f(b-i) \cdot X^{(i-a\cdot s) \cdot (2N/q)}\right)$$

where $(a, b) \in \mathrm{LWE}_s^q(\tilde{m})$, we will extract an LWE ciphertext $(a',b') \in \mathrm{LWE}_{z'}^Q(\mathrm{f}(\tilde{m}))$.

The $N$ components of the mask $a'$ will be the $N$ coefficients of the mask $A$. Additionally, the second component $b'$ of the LWE ciphertext will just be the constant term of the polynomial $B$.

Note that by applying this method we will obtain an LWE ciphertext encrypted under the key $z'=(z_0,-z_{N-1},-z_{N-2},\dots,-z_1) \in \mathbb{Z}_Q^N$, where $z_i$ are the coefficients of the RLWE key $z \in \mathcal{R}_Q$ for $i \in {0,\dots, N-1}$. If we want to obtain an LWE ciphertext encrypted under the original key $z$ (or more precisely, under its coefficients), we can apply a signed permutation to the mask. However, we can also take care of this in the key switching procedure by switching directly from the key $z'$ to the key $s$.

The pseudocode of this method follows:

// Extraction from the Accumulator

input: (A[N], B[N])

output: (a'[N], b')

(a', b') := (A, B[0])

return (A, B) Example: bootstrapped NAND gate

The presented functional bootstrapping in FHEW and TFHE allows one to reduce the noise of a ciphertext while evaluating a negacyclic function $\mathrm{f}$. We will see now how to leverage such a procedure to construct a bootstrapped NAND gate.

In particular, given $(a_1, b_1) \in \mathrm{LWE}_s^q(\tilde{m}_1)$ and $(a_2, b_2) \in \mathrm{LWE}_s^q(\tilde{m}_2)$ we aim to obtain $(a_3, b_3) \in \mathrm{LWE}_s^q(\tilde{m}_3)$, such that $m_3 = m_1 \barwedge m_2$, where $m_1, m_2, m_3 \in {0,1}$.

Recall that $\tilde{m_i} = \lfloor qm_i/t\rceil$ is the encoding of $m_i$ for $i \in {1,2,3}$. Following the procedure of [DM15], we will work with a plaintext modulus of $t=4$.

The idea is to compute the sum of the given ciphertexts:

$$(a_s, b_s) := (a_1, b_1) + (a_2, b_2) \in \mathrm{LWE}_s^q(\tilde{m_s})$$

where $m_s = m_1 + m_2 \in {0,1,2}$ and to take the resulting ciphertext $(a_s, b_s)$ as the input for the functional boostrapping.

Since $m_3$ represents the result of the NAND gate, whenever $m_s=0$ or $m_s=1$, we expect to obtain $m_3=1$, whereas when $m_s = 2$, it should be that $m_3=0$.

The encoding of the values $0$ and $1$ are $\tilde{0} = 0$ and $\tilde{1} = q/4$, which lie in the interval $(-q/8, 3q/8)$. Regarding the value $2$, we have that $\tilde{2} = q/2$, which lies in the other half $(3q/8, 7q/8)$.

Therefore we are looking for a function that maps the interval $(-q/8, 3q/8)$ to $q/4$ (which would be the encoding of the bit 1) and the interval $(3q/8, 7q/8)$ to 0 (which would be the encoding of the bit 0). However, such a function would not be negacyclic, i.e., it would not satisfy the requirement $\mathrm{f}(v + q/2)=-f(v)$.

To fix that issue, we can shift the function by $q/8$ and so work with one mapping $(-q/8, 3q/8)$ to $q/8$ and $(3q/8, 7q/8)$ to $-q/8$.

Finally, we need to take into account that we are looking for a function $f: \mathbb{Z}_q \to \mathbb{Z}_Q$, so we need to rescale the images to $\mathbb{Z}_Q$.

For that reason, we will work with the function $f: \mathbb{Z}_q \to \mathbb{Z}_Q$ defined as

$$x \in [-q/8, 3q/8) \implies f(x)=Q/8$$

and

$$x \in [3q/8, 7q/8) \implies f(x)=-Q/8,$$

where the images of the endpoints have been set to ensure the negacyclic requirement.

Now if we introduce the ciphertext $(a_s, b_s) \in \mathrm{LWE}_s^q(\tilde{m}_s)$ and the function $\mathrm{f}$ into the accumulator, we obtain after the extraction a ciphertext

$$(a_f, b_f) \in \mathrm{LWE}_{z'}^Q(f(\tilde{m}))$$

that encrypts $Q/8$ if the result of the NAND is 1 and $-Q/8$ if the result is 0.

To revert the shift in the function $\mathrm{f}$, we can add a noiseless encryption of $Q/8$ to obtain a ciphertext

$$(a_{f}, b_{f}+Q/8) \in \mathrm{LWE}_{z'}^Q(f(\tilde{m}) + Q/8).$$

Finally, by applying a modulus switch to the key switching modulus $Q_{ks}$, followed by a key switch to the original key $s$, and a final modulus switch to the original modulus $q$, we end up with

$$(a_3, b_3) \in \mathrm{LWE}_s^q(\tilde{m}_3)s.t.m_3 = m_1 \barwedge m_2$$

as we wanted.

Conclusion

FHEW and TFHE stand out for their fast functional bootstrapping procedure that allows one to reduce the noise of ciphertexts while evaluating a function. They can both be described in a unified framework following the approach of [MP21]. In such a framework, they both follow the structure of a first accumulator phase that performs the actual function evaluation and refreshing of the noise, followed by a modulus and key switching phase that transforms the ciphertext into one under the original parameters. The only difference between both schemes under this framework is how they perform the accumulator update or blind rotation. Overall, the functional bootstrapping presented can be leveraged to construct boolean gates such as the bootstrapped NAND gate from the last section.

The description contained in this blog post is a result of analyzing the theoretical description of the schemes, especially the ones found in [DM15] and [MP21], and reverse-engineering OpenFHE's implementation [OpenFHE]. We hope this post helps to bridge the gap between theory and practice that, from our point of view, existed for these schemes.

References

- [AP14] J. Alperin-Sheriff and C. Peikert. Faster bootstrapping with polynomial error. In CRYPTO 2014, volume 8616 of Lecture Notes in Computer Science, pages 297–314, 2014

- [CGGI20] I. Chillotti, N. Gama, M. Georgieva, and M. Izabachène. TFHE: Fast fully homomorphic encryption over the torus. Journal of Cryptology, 33:34–91, 2020.

- [DM15] L. Ducas and D. Micciancio. FHEW: bootstrapping homomorphic encryption in less than a second. In EUROCRYPT (1), volume 9056 of Lecture Notes in Computer Science, pages 617–640. Springer, 2015.

- [Gen09] C. Gentry. Fully homomorphic encryption using ideal lattices. In STOC, pages 169–178. ACM, 2009.

- [GINX16] N. Gama, M. Izabachène, P. Q. Nguyen, and X. Xie. Structural lattice reduction: Generalized worst-case to average-case reductions and homomorphic cryptosystems. In EUROCRYPT 2016, volume 9666 of Lecture Notes in Computer Science, pages 528–558, 2016.

- [GSW13] C. Gentry, A. Sahai, and B. Waters. Homomorphic encryption from learning with errors: Conceptually-simpler, asymptotically-faster, attribute-based. In CRYPTO (1), volume 8042 of Lecture Notes in Computer Science, pages 75–92. Springer, 2013.

- [ACC+18] M. Albrecht, M. Chase, H. Chen, and et al. Homomorphic encryption security standard. Technical report, HomomorphicEncryption.org, Toronto, Canada, November 2018.

- [J22] Joye, M.: SoK: Fully homomorphic encryption over the [discretized] torus. IACR Transactions on Cryptographic Hardware and Embedded Systems, 661–692 (2022)

- [JP22] Joye, M., Paillier, P.: Blind rotation in fully homomorphic encryption with extended keys. In: Dolev, S., Katz, J., Meisels, A. (eds.) Cyber Security, Cryptology, and Machine Learning. CSCML 2022. LNCS, vol. 13301, pp. 1–18. Springer, Cham (2022).

- [LMK+23] Yongwoo Lee, Daniele Micciancio, Andrey Kim, Rakyong Choi, Maxim Deryabin, Jieun Eom, and Donghoon Yoo. Efficient fhew bootstrapping with small evaluation keys, and applications to threshold homomorphic encryption. In Carmit Hazay and Martijn Stam, editors, Advances in Cryptology – EUROCRYPT 2023, pages 227–256, Cham, 2023. Springer Nature Switzerland.

- [LZ22] Zhichuang Liang and Yunlei Zhao. Number theoretic transform and its applications in lattice-based cryptosystems: A survey. arXiv preprint arXiv:2211.13546, 2022.

- [MP21] Daniele Micciancio and Yuriy Polyakov. Bootstrapping in FHEW-like cryptosystems. In Proceedings of the 9th Workshop on Encrypted Computing & Applied Homomorphic Cryptography, WAHC ’21, page 17–28, New York, NY, USA, 2021. Association for Computing Machinery.

- [OpenFHE] OpenFHE - Open-Source Fully Homomorphic Encryption Library. https://github.com/openfheorg/openfhe-development (2023)

- [TFHE-rs] TFHE-rs: Pure Rust implementation of the TFHE scheme for boolean and integers FHE arithmetics. https://docs.zama.ai/tfhe-rs (2023)

- [XZD+23] Binwu Xiang, Jiang Zhang, Yi Deng, Yiran Dai, and Dengguo Feng. Fast blind rotation for bootstrapping FHEs. In Helena Handschuh and Anna Lysyanskaya, editors, Advances in Cryptology – CRYPTO 2023, pages 3–36, Cham, 2023. Springer Nature Switzerland.

- [Chi22] TFHE Deep Dive

—

Previous: Arithmetizing FHE in Circom